The Renters' Rights Act was sold as a landmark reform: stronger protections for tenants, clearer rules for landlords, and a fairer private rental sector. The government promised to end "DIY tenancies" and create security for the 11 million people living in private rented accommodation.

But beneath the headlines lies a troubling paradox. By layering new compliance costs on landlords and estate agents, the Act risks pushing rents higher leaving tenants more vulnerable to poverty and homelessness in a housing market already stretched to breaking point.

🏠 The Protection Paradox

- Compliance costs from new regulations likely to be passed to tenants through rent increases

- Multiple new obligations create "stacked burden" beyond individual merits of reforms

- Rising unemployment and benefit shortfalls make rent increases particularly damaging

- Some landlords may exit market, reducing supply and intensifying competition

- Tenant protections strengthened on paper but affordability eroded in practice

- Policy fails to address systemic housing shortage and market dysfunction

The New Cost Burden

The Renters' Rights Act introduces multiple layers of new obligations that go far beyond the much discussed database fees. While each measure has merit in isolation, together they create a stacked compliance burden that landlords are unlikely to absorb themselves.

Mandatory Compliance Costs

The Act imposes several new financial obligations on landlords:

- Mandatory Ombudsman Membership: Annual fees plus costs for handling tenant complaints

- Database Registration: Fees for maintaining property and landlord information

- Enhanced Insurance Requirements: Higher premiums to cover expanded tenant rights and pet damage

- Professional Training: Compliance courses for landlords and agents on new regulations

- Legal Advisory Costs: Professional guidance to navigate complex new requirements

Decent Homes Standard & Awaab's Law

The extension of quality standards to private rentals creates immediate upgrade costs:

- Urgent Repairs: Addressing previously acceptable but now non compliant conditions

- Insulation Upgrades: Improving thermal efficiency to meet new standards

- Hazard Remediation: Eliminating damp, mould, and other health risks

- Modern Facilities: Upgrading outdated heating, plumbing, and electrical systems

- Regular Inspections: Professional assessments to ensure ongoing compliance

End of Section 21 Evictions

While protecting tenants from arbitrary eviction, this change increases landlord costs:

- Legal Fees: Court proceedings now required for all evictions

- Extended Timelines: Longer possession processes mean lost rental income

- Evidence Requirements: Professional documentation of grounds for eviction

- Risk Premiums: Higher costs to compensate for reduced flexibility

- Void Periods: Longer gaps between tenancies during court proceedings

Administrative Overhead

New procedural requirements create ongoing administrative costs:

- Rent Tribunal Challenges: Administrative overhead for defending rent increases

- Pet Requests: Processing applications and managing pet-related risks

- Anti-discrimination Compliance: Training and procedures to avoid discriminatory practices

- Extended Notice Periods: Longer administrative timelines for tenancy changes

- Written Tenancy Agreements: Professional drafting to meet new requirements

Pass-Through Economics: Who Really Pays?

Economic theory and real-world evidence suggest that compliance costs in regulated markets are typically passed through to consumers. The rental market is no exception.

The Cost Cascade

Compliance costs flow through the rental market in predictable ways:

- Direct Pass-Through: Landlords recoup compliance costs via rent increases

- Estate Agent Fees: Agents raise fees to cover new obligations, which landlords offset by charging tenants more

- Risk Premiums: Uncertainty about future regulations leads to precautionary rent increases

- Market Exit: Some landlords sell up, reducing supply and intensifying competition

- Quality Segmentation: Premium properties absorb costs more easily, pushing budget renters to lower quality options

Market Dynamics

The rental market's structure makes cost absorption by landlords unlikely:

- Demand Exceeds Supply: Housing shortage gives landlords pricing power

- Inelastic Demand: People need somewhere to live regardless of cost

- Limited Competition: Geographic constraints prevent easy substitution

- Information Asymmetry: Tenants often don't understand the cost breakdown

- Regulatory Capture: Large operators can absorb costs better than small landlords

Historical Precedent

Previous rental regulations demonstrate the pass-through pattern:

- Deposit Protection Schemes: Introduction led to rent increases covering membership fees

- Energy Efficiency Standards: EPC requirements drove rent increases in affected properties

- Licensing Schemes: Local authority licensing led to higher rents in covered areas

- Right to Rent Checks: Immigration checks increased administrative costs passed to tenants

The Wider Economic Context

The Renters' Rights Act's cost increases collide with broader economic pressures that make rent rises particularly damaging for tenants.

Labour Market Weakness

ONS figures reveal a deteriorating employment landscape:

- Rising Unemployment: Unemployment climbing toward 5% as economic growth stalls

- Falling Vacancies: Job openings declining for 39 consecutive quarters

- Wage Growth Slowing: Real wage growth failing to keep pace with living costs

- Employment Insecurity: Despite zero-hours contract reforms, many workers still face irregular hours and temporary contracts

- Skills Mismatches: Available jobs don't match unemployed workers' qualifications

Benefit System Inadequacy

The social safety net fails to cover actual housing costs:

- Housing Benefit Caps: Local Housing Allowance rates lag behind market rents

- Universal Credit Shortfalls: Housing element inadequate for actual rental costs

- Benefit Freezes: Years of below-inflation increases have eroded purchasing power

- Administrative Delays: Slow benefit processing leaves tenants in arrears

- Sanctions Regime: Benefit reductions push vulnerable tenants toward eviction

The Squeeze Effect

These trends create a perfect storm for rental affordability:

- Fewer Jobs + Higher Rents = Impossible Math: Government pushes people off benefits into non-existent jobs while rents rise

- Benefit Gaps Widen: As rents increase, the gap between benefits and actual costs grows

- Arrears Accelerate: More tenants fall behind on rent despite having protection from eviction

- Homelessness Risk: Unable to afford private rentals, people face homelessness or overcrowding

- Geographic Inequality: High-cost areas become completely unaffordable for low-income households

The Policy Paradox Unpacked

The Renters' Rights Act embodies a fundamental policy paradox that reveals the disconnect between progressive intentions and market realities.

Rights vs. Reality

The Act creates stronger tenant rights on paper while potentially undermining affordability in practice:

- Protection Paradox: Laws protect tenants from bad conditions but make good conditions unaffordable

- Security Illusion: Tenants gain eviction protection but lose ability to afford rent

- Quality Standards: Higher standards drive up costs, pricing out those who most need protection

- Discrimination Ban: Anti-discrimination rules may be circumvented through higher rents

- Pet Rights: Right to pets comes with insurance costs passed to all tenants

Unintended Consequences

Well intentioned protections may produce counterproductive outcomes:

- Market Segmentation: High-quality rentals become exclusive to high-income tenants

- Underground Economy: Some landlords may operate outside formal regulations

- Geographic Displacement: Renters pushed to lower cost areas with fewer opportunities

- Overcrowding Increase: Multiple families sharing properties to split costs

- Homelessness Acceleration: People priced out of private rentals entirely

Policy Theatre Dynamics

The Act demonstrates classic policy theatre characteristics:

- Visible Benefits: Tenant protections create positive headlines

- Hidden Costs: Rent increases occur gradually and are harder to link to specific policies

- Blame Shifting: Government can blame "greedy landlords" for rent increases

- Complexity Obscures: Multiple factors make it hard to isolate policy effects

- Electoral Timing: Benefits visible before costs become apparent

International Lessons: Rent Control and Regulation

International experience with rental regulation provides valuable lessons about unintended consequences.

Global Examples

Other countries have grappled with similar policy paradoxes:

- Germany: Strict tenant protections but severe housing shortages in major cities

- France: Strong rental regulations but chronic undersupply and high rents

- Sweden: Rent control and tenant rights but decade long waiting lists

- New York: Rent stabilization alongside extreme housing costs and homelessness

- Netherlands: Social housing model with private sector squeezed to premium segment

Common Patterns

Across different contexts, similar dynamics emerge:

- Supply Reduction: Regulation discourages new rental investment

- Market Segmentation: Protected tenants vs. premium market with huge gaps

- Innovation Stifling: Compliance focus reduces efficiency improvements

- Spatial Inequality: Benefits concentrate in already expensive areas

- Generational Unfairness: Existing tenants protected while new entrants face barriers

What's Missing: Structural Solutions

The Renters' Rights Act addresses symptoms rather than causes of the UK's housing crisis, missing opportunities for more fundamental reform.

Supply-Side Interventions

The core problem is housing shortage, not just tenant protection:

- Planning Reform: Streamlining development processes to increase supply

- Land Value Capture: Ensuring development profits fund infrastructure and affordable housing

- Public House Building: Direct government construction to increase supply

- Social Housing Expansion: Alternatives to private rental for low income households

- Institutional Investment: Encouraging large scale professional rental development

Demand-Side Management

Addressing the drivers of rental demand could reduce market pressure:

- Homeownership Support: Help for first time buyers to reduce rental demand

- Benefit Reform: Housing allowances that reflect actual market costs

- Employment Policy: Job creation to reduce benefit dependency

- Regional Development: Economic opportunities outside expensive areas

- Immigration Management: Coordinating housing supply with population growth

Market Structure Reform

More fundamental changes could address market dysfunction:

- Rent Stabilization: Limiting rent increases to inflation plus modest premium

- Speculation Taxes: Discouraging property investment purely for capital gains

- Professional Standards: Licensing landlords rather than just adding compliance requirements

- Cooperative Models: Tenant ownership and community land trusts

- Public Options: Government provided rental alternatives to private market

Economic Modeling: Quantifying the Impact

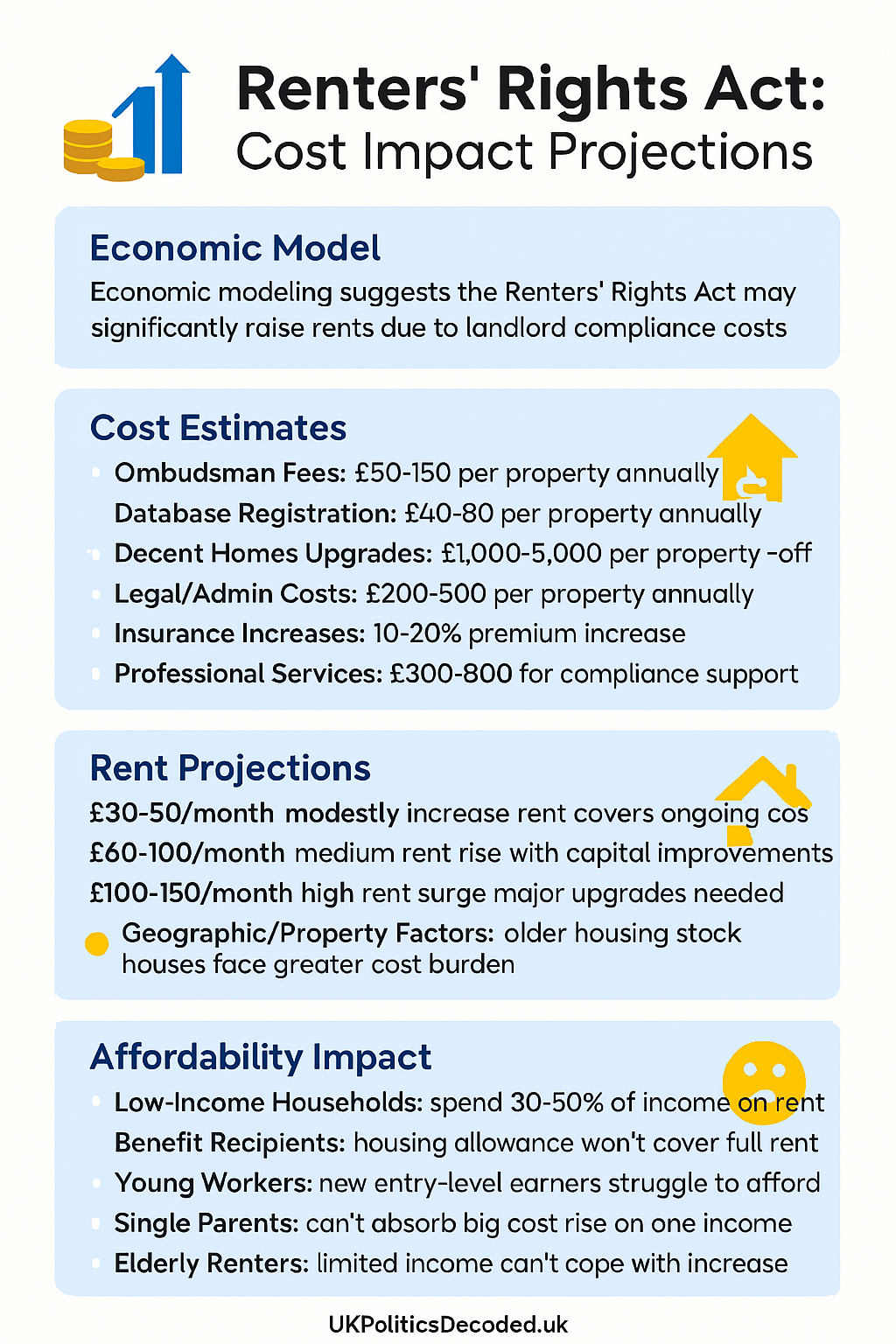

While precise figures are difficult to calculate, economic modeling suggests significant rent increases are likely.

Projected rent increases across different scenarios, showing how compliance costs cascade through the rental market to affect tenant affordability.

Cost Estimation

Industry estimates suggest substantial compliance burdens:

- Ombudsman Fees: £50-150 annual per property

- Database Registration: £40-80 per property annually

- Decent Homes Upgrades: £1,000-5,000 per property one-off

- Legal and Admin Costs: £200-500 per property annually

- Insurance Increases: 10-20% premium increases

- Professional Services: £300-800 per property for compliance support

Rent Increase Projections

Translating costs to rent increases across different scenarios:

- Modest Estimate: £30-50 per month increase to cover ongoing costs

- Medium Estimate: £60-100 per month including capital improvements

- High Estimate: £100-150 per month in areas requiring major upgrades

- Geographic Variation: Higher increases in areas with older housing stock

- Property Type Impact: Larger increases for houses vs. purpose built flats

Affordability Impact

Rent increases will disproportionately affect vulnerable tenants:

- Low-Income Households: 30-50% of income already spent on housing

- Benefit Recipients: Housing allowance won't cover increased costs

- Young Workers: Entry-level wages insufficient for higher rents

- Single Parents: Limited income flexibility to absorb increases

- Elderly Renters: Fixed incomes unable to accommodate cost rises

Regional and Demographic Impacts

The protection paradox will affect different groups and areas unequally, potentially exacerbating existing inequalities.

Geographic Variation

Some regions will experience larger rent increases than others:

- Northern England: Older housing stock requiring more upgrades

- London: High base rents amplify percentage increases

- Seaside Towns: Large private rental sectors with compliance challenges

- University Cities: Student rental market particularly affected

- Post-Industrial Areas: Lower incomes make rent increases especially painful

Demographic Differences

Certain groups face disproportionate impacts:

- Young Adults: Higher rental dependency, lower incomes

- Ethnic Minorities: Greater reliance on private rental sector

- Disabled People: Limited housing options, benefit dependency

- Single-Person Households: Cannot share costs, vulnerable to increases

- Recent Migrants: Limited access to social housing, rental market dependent

Intersectional Vulnerabilities

Multiple disadvantages compound the protection paradox:

- Young + Ethnic Minority + Low Income: Triple vulnerability to rent increases

- Disabled + Single + Elderly: Limited options for cost reduction

- Female + Single Parent + Benefits: Constrained income, flexible housing needs

- Student + Young + Part-time Work: Precarious income, limited alternatives

Alternative Approaches: Learning from Success

Some jurisdictions have found ways to improve rental markets without creating affordability crises.

Vienna Model

Vienna's approach combines public provision with private regulation:

- Social Housing Majority: 60% of residents in public/social housing

- Mixed Income: Middle class access prevents residualization

- Quality Standards: High standards without cost pass-through

- Private Sector Discipline: Public options constrain private rent increases

- Long-term Investment: Municipal housing development reduces market pressure

Singapore Model

Singapore combines homeownership with rental regulation:

- Public Housing Majority: 80% homeownership via public development

- Regulated Private Sector: Small but well regulated rental market

- Supply Management: Government controls land release and development

- Affordability Targets: Housing costs capped as percentage of income

- Integrated Planning: Housing, transport, and employment coordinated

German Lessons

Germany's experience offers both warnings and models:

- Rent Brake Success: Some cities have limited rent increases effectively

- Supply Shortage: But regulation has discouraged new rental construction

- Quality vs. Quantity: High standards but insufficient supply

- Cooperative Sector: Housing cooperatives provide middle path

- Professional Management: Large scale professional landlords more efficient

Recommendations: Breaking the Paradox

Avoiding the protection paradox requires coordinated policy reform across multiple areas.

Immediate Mitigations

Short-term measures could reduce the rent increase pressure:

- Phased Implementation: Gradual introduction to spread upgrade costs over time

- Landlord Support: Grants or low interest loans for Decent Homes upgrades

- Benefit Increases: Housing allowance rises to match rent increases

- Rent Stabilization: Temporary limits on rent increases during transition

- Supply Incentives: Planning fast track for new rental developments

Medium-term Reforms

Deeper changes could address structural problems:

- Social Housing Expansion: Large scale public house building program

- Employment Policy: Job creation to reduce benefit dependency

- Planning Reform: Streamlined approval for rental developments

- Tax Reform: Land value taxation to encourage efficient use

- Regional Policy: Economic development outside expensive areas

Long-term Transformation

Fundamental reform could create a genuinely affordable rental sector:

- Public Option: Government provided rental housing for all income levels

- Cooperative Development: Tenant owned housing cooperatives

- Land Reform: Community land trusts and public land banking

- Financial Reform: Alternative funding models for housing development

- Economic Democracy: Worker ownership reducing income inequality

Conclusion: Policy Theatre or Genuine Reform?

The Renters' Rights Act exemplifies a recurring problem in British policymaking: progressive rhetoric masking regressive outcomes. By focusing on tenant protections while ignoring market dynamics and affordability, the Act risks becoming another chapter in Britain's housing crisis policy theatre that makes problems worse while claiming to solve them.

The protection paradox at the heart of this legislation reveals the fundamental weakness of attempting piecemeal reform in a systemically broken housing market. You cannot regulate your way to affordability when the core problem is scarcity. You cannot protect tenants with rights they cannot afford to exercise.

The compliance costs embedded in this Act from ombudsman fees to mandatory upgrades may seem modest in isolation, but their cumulative impact threatens to price out the very people the legislation claims to protect. When landlords face higher costs, those costs get passed to tenants through higher rents. This is not landlord greed; it is basic economics.

The timing makes this particularly cruel. As unemployment rises and benefit adequacy erodes, government policy is simultaneously pushing people off welfare into a shrinking job market while making housing more expensive. The mathematical impossibility of this approach seems lost on policymakers convinced that good intentions can overcome market forces.

Most troubling is the opportunity cost. The political capital and legislative time spent on this Act could have been used for genuine solutions: large scale public house building, planning reform to increase supply, or benefit systems that reflect actual housing costs. Instead, we get symbolic protections that may accelerate the poverty they claim to address.

The international evidence is clear: successful rental markets require either massive public provision (like Vienna) or coordinated supply and demand policies that address affordability directly. Regulation alone, however well-intentioned, cannot solve a supply crisis and may make it worse.

Britain's renters deserve better than this protection paradox. They need homes they can afford, not rights they cannot exercise. They need a government that understands housing as economics, not just politics. Until policymakers grasp this fundamental distinction, each new "landmark" reform will simply add another layer of cost to an already unaffordable crisis.

The Renters' Rights Act may go down in history as the moment good intentions collided with economic reality and economic reality won. The question is whether future governments will learn from this failure or repeat it with even more elaborate protections that protect nobody from the harsh mathematics of housing scarcity.

Rights without affordability are not rights at all they are promises the state cannot keep and burdens the market will not bear. The protection paradox teaches us that sometimes, the best way to help people is to resist the urge to regulate and instead address the underlying problems that regulation cannot fix. In Britain's broken housing market, that means choosing supply over symbolism, economics over politics, and genuine solutions over comfortable illusions.